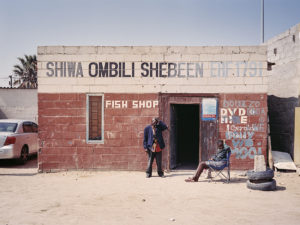

The photographic work “Shebeen Queens“ explores the bar culture of the townships in South Africa and Namibia and focuses on its role as a sociocultural phenomenon with ambivalent connotations. This ambivalence is closely linked to the disenfranchisement and oppression of the local population by the apartheid regime and not least by the colonial rule of the German Empire. The term “shebeen” – which was originally derived from the Irish word ’sibín‘ – refers to a type of improvised tavern which sells alcohol without a valid licence in southern African countries. In the midst of an otherwise largely patriarchal society, so-called Shebeen Queens run these bars as self-made entrepreneurs. Through this work, I aim to capture the different stories of these strong women.

The origins of the shebeens date back to the 19th century. Due to colonial politics and apartheid, these places initially served as a refuge for indigenous people, who were persecuted in the public sphere. Because of the discriminatory legal situation, the local population had to look for loopholes: They found them in the living rooms of their own homes, where women often began to produce and serve their own alcohol. As discrimination ramped up with increasingly severe apartheid laws, these places often became the only social gathering places for the oppressed locals. The tavern keepers, who were given the nickname shebeen queens, eventually became important pillars within individual communities.

In the townships, shebeens are often one of the few available places for social gatherings, and as such they become the go-to spot for a large part of the population seeking to escape the monotony of everyday life. But this quality is also what often becomes the trigger for a vicious cycle, as many come to these places to drink away their already meagre wages. Ultimately, the historical social imbalances caused by colonial and apartheid policies are reproduced and exacerbated by this dilemma.

But it would be unjust to simply reduce the shebeens to their frequently discussed legal status or to the social ills they’re associated with. My photographs resists the temptation of such stereotyping. After all, these are also places where women, despite the most difficult conditions, have set up their own businesses and manage to provide for their families.

In the same way that „Shebeen Queens“ does not intend to reproduce a cliché, the work also does not attempt to romanticise the bar culture in the townships of South Africa and Namibia. On the one hand, the pictures represent a certain subculture and a sense of emancipation; on the other hand, they act as a kind of magnifying glass under which the fatal socio-economic effects of oppressive colonial and apartheid policies become more concentrated. With this in mind, it’s all the more essential that the photographs help, above all, to raise the voices of the individual women who stand behind the shebeens and find themselves on the threshold between self-determination in the midst of a male-dominated society and economic hardship.